Last Saturday I went for a field trip organized by the Centre for Education and Research in Geosciences. This is an outreach effort initiated by geologists Dr. Sudha Vaddadi and Natraj Vaddadi along with the student community from various Pune colleges. They undertake these programs regularly through the year. We explored the Deccan Plateau region northeast of Pune.

On Pune Nasik Highway we turned east at Ale Phata. Our first stop was a little past Gulunchwadi . Across the road an inclined dike intruding into older basalt flows is visible. And a groundwater seep is seen along the contact between two basalt flow units.

Such water seeps can slowly weather and remove rock eventually creating larger passages and undercuts. We saw that just a few minutes ahead. Besides a small roadside temple is a steep stairway leading you into a streambed below. There you come across a wondrous natural arch.

I am not sure I have a good explanation of how exactly this feature formed. Was there a larger waterfall cascading from the top before? At the same time, groundwater seeping along the contact between the two flow units would have eroded rock material creating large passageways which eventually coalesced. Stream flow got directed along the bed of this large tunnel. Further down cutting by the stream has lowered the level of the stream bed, leaving a stranded 'bridge'.

Also notice in the satellite picture below that the stream makes an abrupt turn at a couple of different points along its course. Its pathways appear to be controlled by fractures.They would have provided weak zones that focused and enhanced erosion.

From this site we proceeded to Mandahol Dam. A little north of this dam is a ridge line named Mhasoba Zap. Can you spot something unusual in the topography of the ridge?

The sinuous feature is an exhumed river of lava! It erupted between 67 and 66 million years ago.

Basalt lava is less viscous and can flow for long distances. It can follow a preexisting valley or lows in the landscape, forming a lava channel. The image below is from a USGS monitoring station that has captured a lava channel formed during a recent eruption in Hawaii.

The view in this photo at Mhasoba Zap is looking upslope. The winding ridge which you can follow up to the isolated hill in the background is the exhumed lava channel. It stands out about 50-100 meters above the adjacent plains.

And here is the lava channel looking downslope. It continues for a distance of about 3 kilometers 'downstream' before dying out.

The margin of the channel (white arrows) are made up of a basalt which looks a little different from the basalt in the central parts of the channel. The margin rock is reddish in color. A closer look (in the field) will tell you that it is glassy to fine grained. Lava at the margins cools quickly. This cooled lava gets broken up because of the stresses imparted by flowing lava in the center of the channel. This gives a fragmented character to the margins. The iron in the quenched glassy matrix rusts to impart a orange red hue to the rock.

In a close up I have outlined the base of the channel in orange lines. Dr. Sudha Vaddadi who has mapped this region when she was working with the Geological Survey of India tells me that this entire ridge is actually a lava tube. The top has been eroded away! She was able to identify the 'roof' a km away downslope.

Lava at the surface cools and solidifies quickly. That leaves a tube or a pipe through which lava is supplied from the vent across long distances. The solid crust insulates and keeps the interior hot, allowing the lava to reach long distances from its source. The photo is of a lava tube from the Reunion Islands, a site of ongoing volcanism.

Let's take a closer look at the margin rock. It is distinctive due to the reddish color and the fractured fragmented nature of the rock. It has also been extensively affected by secondary mineralization. Cracks are filled with (white veins) of fibrous scolecite (zeolite family) and calcite.

Blobs and lava spatter accumulates at the margins, cooling and welding together to form an 'agglomerate'. The close up shows globular masses of lava stuck together.

In this synoptic view, almost the entire lava channel is visible. Downslope it breaks up into distributary 'fingers'.

This really was a fun trip. From this lava ridge we traveled south and saw stalactites at the Duryabai Temple near Wadgaon Durya and then went further south to see the famous potholes in the Kukdi river bed near Nighoj village. I will write about these features in a later post.

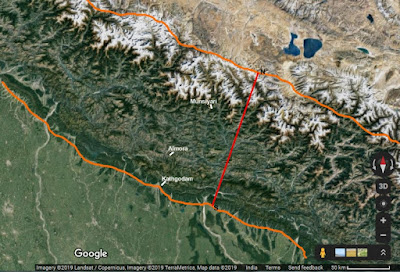

In the embedded map look for Malaganga Temple, Mhasoba Zap, Wadgoan Durya and Nighoj.

Email subscribers may not be able to see the map. Follow this Permanent Map Link.

Although the Western Ghat escarpment with its spectacular views captures a lot of attention, the Deccan plateau region to the east and northeast of Pune has a lot of interesting geology and landscapes.

Get out there and explore!

On Pune Nasik Highway we turned east at Ale Phata. Our first stop was a little past Gulunchwadi . Across the road an inclined dike intruding into older basalt flows is visible. And a groundwater seep is seen along the contact between two basalt flow units.

Such water seeps can slowly weather and remove rock eventually creating larger passages and undercuts. We saw that just a few minutes ahead. Besides a small roadside temple is a steep stairway leading you into a streambed below. There you come across a wondrous natural arch.

I am not sure I have a good explanation of how exactly this feature formed. Was there a larger waterfall cascading from the top before? At the same time, groundwater seeping along the contact between the two flow units would have eroded rock material creating large passageways which eventually coalesced. Stream flow got directed along the bed of this large tunnel. Further down cutting by the stream has lowered the level of the stream bed, leaving a stranded 'bridge'.

Also notice in the satellite picture below that the stream makes an abrupt turn at a couple of different points along its course. Its pathways appear to be controlled by fractures.They would have provided weak zones that focused and enhanced erosion.

From this site we proceeded to Mandahol Dam. A little north of this dam is a ridge line named Mhasoba Zap. Can you spot something unusual in the topography of the ridge?

The sinuous feature is an exhumed river of lava! It erupted between 67 and 66 million years ago.

Basalt lava is less viscous and can flow for long distances. It can follow a preexisting valley or lows in the landscape, forming a lava channel. The image below is from a USGS monitoring station that has captured a lava channel formed during a recent eruption in Hawaii.

The view in this photo at Mhasoba Zap is looking upslope. The winding ridge which you can follow up to the isolated hill in the background is the exhumed lava channel. It stands out about 50-100 meters above the adjacent plains.

And here is the lava channel looking downslope. It continues for a distance of about 3 kilometers 'downstream' before dying out.

The margin of the channel (white arrows) are made up of a basalt which looks a little different from the basalt in the central parts of the channel. The margin rock is reddish in color. A closer look (in the field) will tell you that it is glassy to fine grained. Lava at the margins cools quickly. This cooled lava gets broken up because of the stresses imparted by flowing lava in the center of the channel. This gives a fragmented character to the margins. The iron in the quenched glassy matrix rusts to impart a orange red hue to the rock.

In a close up I have outlined the base of the channel in orange lines. Dr. Sudha Vaddadi who has mapped this region when she was working with the Geological Survey of India tells me that this entire ridge is actually a lava tube. The top has been eroded away! She was able to identify the 'roof' a km away downslope.

Lava at the surface cools and solidifies quickly. That leaves a tube or a pipe through which lava is supplied from the vent across long distances. The solid crust insulates and keeps the interior hot, allowing the lava to reach long distances from its source. The photo is of a lava tube from the Reunion Islands, a site of ongoing volcanism.

Photo Credit: Nandita Wagle

Let's take a closer look at the margin rock. It is distinctive due to the reddish color and the fractured fragmented nature of the rock. It has also been extensively affected by secondary mineralization. Cracks are filled with (white veins) of fibrous scolecite (zeolite family) and calcite.

Blobs and lava spatter accumulates at the margins, cooling and welding together to form an 'agglomerate'. The close up shows globular masses of lava stuck together.

In this synoptic view, almost the entire lava channel is visible. Downslope it breaks up into distributary 'fingers'.

This really was a fun trip. From this lava ridge we traveled south and saw stalactites at the Duryabai Temple near Wadgaon Durya and then went further south to see the famous potholes in the Kukdi river bed near Nighoj village. I will write about these features in a later post.

In the embedded map look for Malaganga Temple, Mhasoba Zap, Wadgoan Durya and Nighoj.

Email subscribers may not be able to see the map. Follow this Permanent Map Link.

Although the Western Ghat escarpment with its spectacular views captures a lot of attention, the Deccan plateau region to the east and northeast of Pune has a lot of interesting geology and landscapes.

Get out there and explore!