Carl Simpson and Jeremy B.C. Jackson, in an essay titled Bryozoan Revelations for Science Advances, sketch out the important biological aspects of bryozoans, a type of marine invertebrate.

From their article:

"Bryozoans are neglected children of the sea floor. Google corals and you get nearly 4 billion hits, whereas bryozoans get just 4 million. This disparity reflects the enormity and notable beauty of coral reefs and extraordinary diversity of associated species that have long attracted intense scientific research. Yet for all their grandeur, corals occupy less than a tiny fraction of 1% of the global ocean, whereas bryozoans extend from the equator to the poles and intertidal to abyss. Bryozoans are species-rich. As a group, they have at least 10 times more species than corals. They also have a more extensive and continuous fossil record and have been major components of vast seafloor communities for half a billion years".

The enormous diversity of bryozoan skeletal shapes and their abundance as living communities and as fossils from the late Cambrian onwards make it possible to use them to understand evolutionary questions such as timing of origins, rates of change, convergent evolution, and origin of variable form in animal communities. This succinct essay summarizes these lines of research quite well.

As a sedimentologist my interest in these organisms was the role they played as sedimentary particles. Bryozoans, along with echinoids and brachiopods, were among the most common sea floor inhabitants of Paleozoic shallow marine realms. They made up a large proportions of the sediment that formed by the disintegration of shells and skeletons of sea creatures.

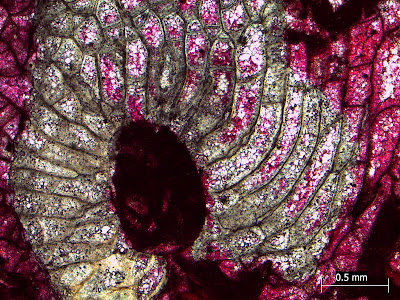

A typical bryozoan skeleton has a trellis like appearance. Bryozoans are colonial organisms building a lattice like structure with the animal living in chambers called zooids. It is these zooids that was my main interest, or rather what I could see inside them. The animal was long gone, decayed away, but the chamber or cavity was filled with different types of calcite, archiving the process of the transformation of loose sediment into rock. Through geologic history different types of fluids had entered the open spaces within the skeleton and precipitated different types of calcite. Petrologists can infer the changing geochemical conditions as sediments get buried and importantly trace the changes in open spaces, or porosity, as fluids either dissolve sediment or deposit new minerals, information that is useful to the petroleum industry.

I will share a couple of examples of these diagenetic changes observed inside a zooid.

This thin section of a limestone from the Middle Ordovician strata of the southern Appalachian mountains has been stained using a mixture of Alizarin Red-S and Potassium Ferricyanide. The pink is an iron free calcite. The purple in the center of the zooids is an iron rich calcite. This sequence from an iron free to an iron rich calcite indicates oxygen poor reducing conditions upon burial, a chemical environment in which iron can enter the growing calcite crystal.

And in this thin section the pale bronze colored mineral highlighting the skeletal frame is chert, a variety of silica that has partially replaced the calcite skeleton. The replacement process has been quite delicate, preserving the original structure of the skeleton.

Evolution is not the only story that bryozoans reveal.