By 2.3 billion years ago, cyanobacteria employing oxygenic photosynthesis began proliferating in the world's oceans. This resulted, several hundreds of millions of years later, in triggering the formation of fold mountain belts in places where tectonic plates converge and collide.

This big idea linking geological processes and biological evolution is explored in an interesting paper by John Parnell and Conner Brolly published in Communications Earth and Environment.

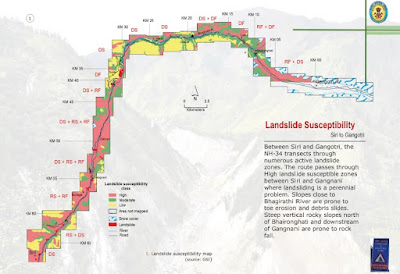

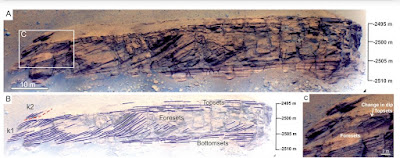

Source: Examining the tectono-stratigraphic architecture, structural geometry, and kinematic evolution of the Himalayan fold-thrust belt, Kumaun, northwest India- S Mandal et.al. 2019.Consider how fold mountain grow using this example from the Lesser Himalaya. The different colored layers are rocks formed on the northern margin of the Indian plate. They range from 1.8 billion years to around 50 million years in age. As the Indian continent collided with Asia around 50 million years ago, this pile of metamorphic and sedimentary rocks was squeezed by compressional forces. They were folded and broken up by thrust faults into a series of panels or sheets. Deformation of the Indian plate spread from north to south. As you gaze from the top to the bottom of the graphic you will notice that folding and faulting first began at the zone of collision (extreme right of the graphic). Over time the locus of deformation migrated further and further away from the site of continental contact. New faults grew and moved sheets of rocks southwards, stacking them and building mountains by thickening the crust.

Now look at the more detailed cross section below from Mandal's paper. The fold and thrust architecture of Lesser Himalaya is clearly revealed. The thin pink lines are the thrust faults and they have partitioned the rock pile into a series of panels (A-G), causing 'stratigraphic repetition' across the mountain belt. Internally, each panel has the same sequence of layers. I am ignoring some of the complexities of the formation of the Greater Himalaya for the sake of brevity.

Parnell and Brolly argue that the increased biomass in oceans starting 2.3 billion years ago produced organic rich sediment, which transformed on burial into carbonaceous shale and graphite bearing metamorphic rocks. The rates at which tectonic plates move meant that basins that filled up with such sediments began arriving at collisional zones some 200 million years since their initiation.

Carbon rich and graphite bearing layers reduce friction along faults making the contractional deformation I outlined in the Himalaya example easier. The widespread mountain building activity observed in the geological record from 2 to 1. 8 billion years ago was helped along by faults preferentially splitting the rock pile along weaker graphite rich layers with the carbonaceous material acting as a lubricant, allowing easier movement and stacking of the faulted blocks. The nice graphic below compiles instances of mountain building that took place during that time frame from across the globe.

The authors give several examples of Paleoproterozoic orogenic belts in which major fault zones are associated with graphite rich layers. They also point out that the atomic arrangement of carbon in graphite that has been disturbed by faulting is different from the background graphite in sediment. Many fault zones in their examples contain this 'disordered' graphite bolstering their case that graphite was mobilized during fault movement.

This connection between carbon rich sediment and faulting appears as a recurring theme in geologic history. Another example comes from the Cretaceous when there was abundant deposition of organic rich sediment during times of globally high sea levels and oxygen depleted ocean depths. The resulting black shales subsequently provided the weak zones for faults to split and move crustal sheets during the building of the Rockies, the Andes and other mountain ranges spread widely across continents.

While it makes sense that carbonaceous material will reduce frictional resistance and enhance fault movement, one must be careful not to overemphasize the causal link between carbon rich sediment and mountain building. After building a case for the close association of carbonaceous sediments and major faults, the authors write, "Given the link between organic matter and deformation evident in younger rocks, the scene was set for collisional orogenesis at ~2 Ga (Fig. 1) by the exceptional accumulation of organic carbon during the mid-Palaeoproterozoic.

I would think that 'the scene was set for collisional orogenesis at ~2 Ga' not because of the presence of carbon rich sediment, but because by that time a global plate tectonic regime was operating and plate forces were maneuvering continents in directions that resulted in them converging at multiple places. The pulse of mountain building during that time period occurred because several continents crashed into each other.

That the presence of carbonaceous sediment may aid faulting but is not a necessary condition for thrust fault regimes to develop in convergent settings is supported by looking at what occurred earlier in geologic history before the exceptional bloom in cyanobacterial growth and carbon burial. Yatin Zong and colleagues in a recent paper published in Nature Communications describe the formation of the Central Orogenic Belt of Northern China which formed by the collision of a chain of oceanic volcanoes with the North China continent in Neoarchean times (2.8-2.5 billion years ago). They demonstrate the development of fold and thrust structures and large distance movement along thrust faults that occurred in this convergent plate setting along the North China continental margin between 2.6 and 2.5 billion years ago. Here, thrust faulting detached sheets of the crust made up of lava erupted from oceanic volcanoes and also sediments deposited in adjacent basins and moved them hundreds of kilometers. The fault surface was lubricated by copious amounts of the shiny mineral mica.

This is several hundred million years before the exceptional accumulation of carbonaceous sediment in Paleoproterozoic times. It appears that the lithosphere deforms in a mechanically consistent style under the horizontal compressive forces prevalent in plate tectonic settings, with hydrated oceanic crust, water saturated clays, micas, and carbon being alternative candidates for reducing friction.

How did the outer shell of the earth behave before plate tectonics? Early earth was a much hotter place. Warm rocks are weak. Plate motion is driven by a pull force that is imparted as a tectonic plate subducts or sinks underneath another tectonic plate. So, for plate tectonics to evolve, the lithosphere or the outer shell of the earth has to become strong enough not to disintegrate as it is being pulled by its subducting leading edge. Such conditions, geologists think, likely became more and more common as the earth cooled sufficiently by about 3 billion years ago.

Before this time tectonics played out as gravity driven vertical movements of the crust . This inference is based on the structures observed in many Archean age terrains which show large granitic bodies encircled by steeply tilted and metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks. On a hotter earth, buoyant granitic magmas rose and intruded the near-surface volcanic and sedimentary layers pushing them aside and thermally transforming them into low grade metamorphic rocks.

This ensemble of metamorphosed volcanic and sedimentary rocks are called greenstones. The typical structure is a granitic dome encircled by vertically oriented layers of greenstone having a flattened or schistose fabric formed due to the parallel orientation of platy minerals like micas and chlorite. The satellite image below shows one of the classic examples of this 'dome and keel' structure from the Archean age terrain of Pilbara from northwest Australia. Grey green narrow schist belts are wedged between light colored oblate shaped granitic domes. The Pilbara terrain ranges in age from 3. 5 billion to 2. 9 billion years.

The Indian continental crust has its share of these Archean granite-greenstone associations. Some prominent ones are in Karnataka, exposed near Dharwar, Shimoga and Kolar. Most of these belts are older than 3 billion years in age.

Contrast this structural style with that of a classic fold belt from younger Proterozoic times. These are the famous Nallamala ranges in south India formed by horizontal compressive forces.

The earth changed considerably between 3 and 2 billion years ago. Chemical differentiation of magmas separated heavier elements from the lighter ones, forming continents made up of lighter buoyant granitic rocks and oceanic depressions floored by denser basalt lava. The growing mechanical strength of its outer shell formed coherent slabs or plates ultimately resulting in the more familiar plate tectonic cycles of super-continent formation and breakups.

Another striking change appeared on the surface by 2 billion years; the formation of high topography. In the Archean, growth of new crust by constant injections of magma kept the outer shell warm and weak, unable to support the weight of tall mountains. As the earth cooled the lithosphere gained strength and became rigid. High mountains built by tectonic thickening of the crust at continent collision zones could now stand on a strong foundation.

Folds, faults, crushed rocks, and mountain belts. All these dramatic contortions of the crust readily invite us to probe the physical evolution of the lithosphere as an explanation for the geological dynamism of our planet. Parnell and Brolly in their paper remind us that unique biological events have played a role too in shaping earth's physical features, even those as immense as the Himalaya.

*******************

Wishing readers a very Happy and Safe New Year!